By John Jones, JD, PhD

Out of the News Already?

Back in early June 2021, news reports claimed that India was under siege, from an invisible enemy (aka a virus), that affected practically no one (a mere 5 per 100,000). Now it is July, and India matters not. What happened? What should we know? What patterns can we see?

Are Epidemics Just Relative Numbers?

In 2020, approximately 3,360,000 deaths occurred in the United States. The CDC says that from 2019 to 2020 there was a noticeable increase in the American death rate, from 715 to 829 deaths per 100,000 people. Is that what they mean (meant) by epidemic? The level of 829 deaths per 100,000 is not even highest in the last decade, but what about other countries? You know, those poor, backward, Trump-hole, socialist (or insert your favorite pejorative here), nations? Surely, the fog of Covid is sweeping through them, right?

It turns out that many countries have lower rates of death, and far fewer Covid deaths – than what is seen in the United States. And please appreciate, the all-cause mortality-rate is more important than any counts of so-called Covid numbers – be they defined as cases (symptomatic or asymptomatic), clinical or lab-confirmed, infections or deaths (by versus with).

Let me explain. Different countries have varied standards as to what constitutes a diagnosis of Covid. Hence, across the world, there is no uniform definition of a Covid death (motorcycle accidents excepted). Furthermore, some places, like China, allow doctors to treat Covid patients (and others) with vitamin C, vitamin B, zinc, and selenium. In parts of Africa, Ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine are purchased cheaply, without a doctor’s note, at the pharmacy. Such practices affect health outcomes and overall mortality rates.

But the strongest correlate of death, in any country, is the make up of their age cohorts. Put simply, the larger the proportion of elderly, the more often that people die from respiratory illness, cancer, heart disease, diabetes, etc. If we exclude infant and childhood mortality, those in younger age cohorts have far lower probabilities of dying from any so-called disease.

Would You Rather Live in India or Die in a Richer Country?

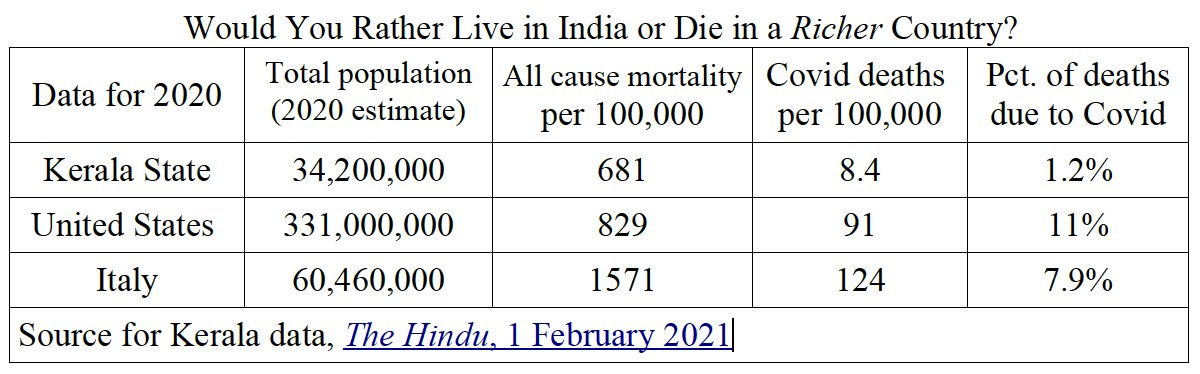

Consider this table, comparing the Indian State of Kerala (with a population comparable to places like California, Peru, Canada or Uzbekistan) with the United States and Italy. What can explain the differences in all-cause mortality and Covid deaths?

With a population of around 60 million, Italy is the epitome of a demographic crisis. Nearly one-quarter of its people are between ages 45-60; it also has about 16 million people between ages 60-85; aka in the Covid-hot zone. Conversely, in India, with 1.3 billion people, less than 15% are ages 55 and older.

If we compare the United States or Italy to the southern Indian state of Kerala, we see the noticeable relationship between age-cohorts (the so-called population pyramid), death rates in general, and Covid deaths in particular. Kerala has barely 12% of its population over age 60, but more than 50% of its residents are under age 25.

According to the CDC, in the United States for 2020, the death rate for people age 85 and older was 15% (15,000 per 100,000); and per 100,000 Americans who were age 85 and over, nearly 1,800 died with a respiratory ailment. (Recall, recently the CDC invented a new category of death called PIC – they just lumped together any and all types of respiratory distress as pneumonia, influenza-like illness, and Covid-like illness).

So What about India?

Starting from our nuanced perspective, now let’s delve into India. To believe those recent headlines, you might think that India, at least since March 2021, is suffering a fate worse than Europe during the Black plague, back in the late medieval period, a time when people had no electricity, no running water, and gasp, no internet.

India has a population of over 1.3 billion people – more than four times the United States. And just as there are significant economic, social, and geographic differences within the United States, the diversity in India surpasses what most of us can imagine. India is a land of billionaires and extreme poverty. The high-tech industry and megacities are littered with people sleeping outside, and trash heaps in front of suburban palatial estates. Hundreds of millions live along tropical coastal beaches, while equal numbers live in northern climes, and cities polluted with car exhaust.

Just as in America, when crowded, polluted, and colder cities, like New York City, gave us the bulk of Covid reports, and Southern, warmer states had far lower numbers, the same is true in India. Their Covid cases are clustered.

As Jo Nash explains,

“it is [inappropriate] to talk about India as a homogenous nation-state given the country’s vast landmass and a population that crosses six climate zones. Indians live in vastly different environmental conditions depending on their location. [There are no national] public health conditions in India … in any meaningful sense.”

She continues,

“The COVID [sic] outbreaks have tended to cluster in urban areas, especially the megacities of Mumbai (Bombay), New Delhi, Kolkata (Calcutta), Bengaluru (Bangalore), and Chennai, then it makes sense to look at the problem of air pollution and its impact on respiratory health in those areas.”

Before February 2021, and the start of Covid vaccination campaigns in India, Covid deaths across India were extremely low – compared to other nations around the world. As noted above, the numbers follow the demographics – but not all parts of India are the same. Hence, wherever the population was relatively older, and the proportion of youth are smaller, the deaths were higher. For example, in the megacity of Mumbai, 2020 saw an all-cause mortality rate at 869 per 100,000, which is comparable to the United States.

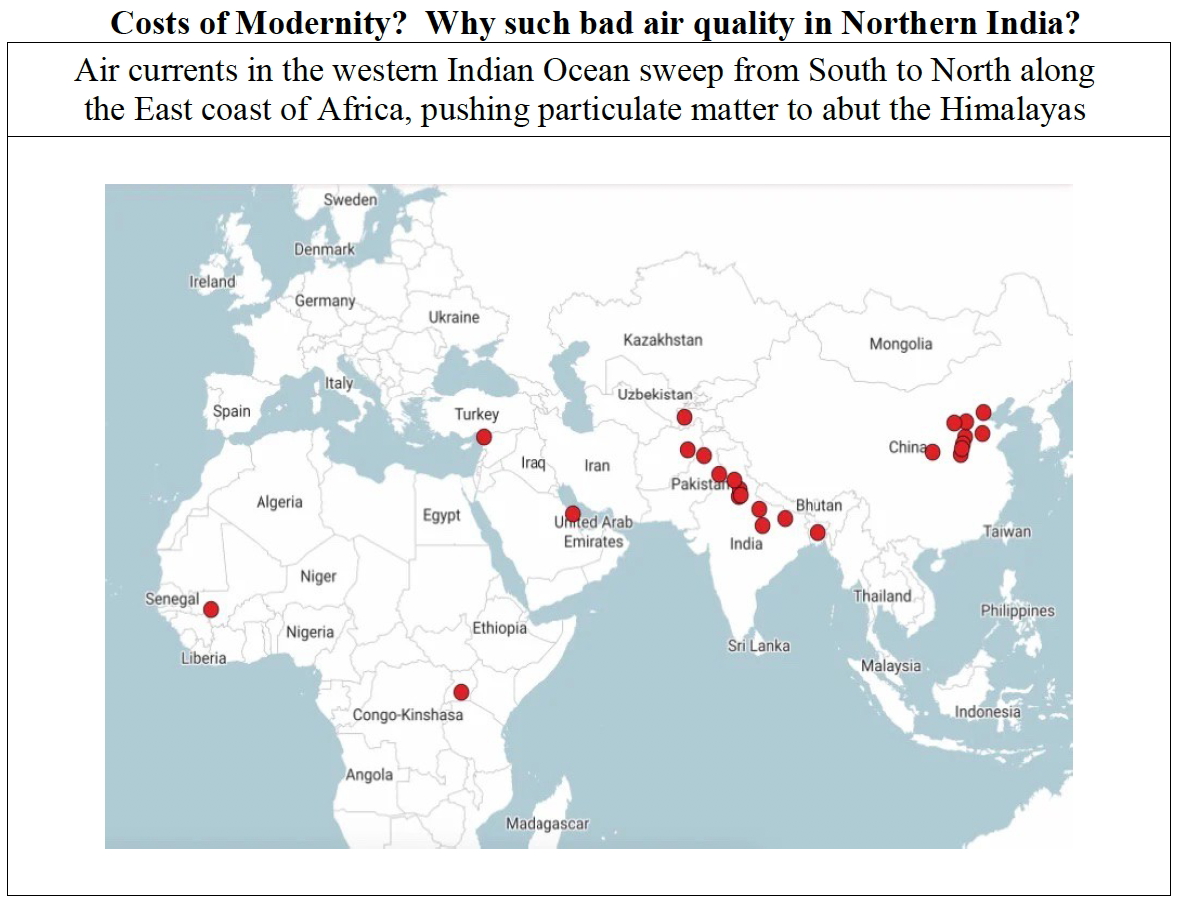

Like most modern megacities (Beijing, Los Angeles, Lima, Peru, Lahore, Pakistan), Delhi has toxic air which, in the past, moved local government to impose city-wide shutdowns due to the high numbers of people suffering respiratory events. According to Nash (2021), more recent media images of people “lying on the ground, gasping for air, outside overflowing hospitals were from New Delhi, [a city in] which [the population] often battles with surges in respiratory crises,

when pollution poses a significant danger to life.”

The worst times are generally during the intense dry and hot season before the monsoon (April and May); and November and December in Haryana and the Punjab (to the Northwest of Delhi) – when farmers burn the fields just before planting season. That winter burn “creates a lot of smoke that settles into a thick smog that envelops Delhi.” And as we might expect, in Delhi and northern India, the poor suffer disproportionately.

Nash (2021) says that her contacts in the northeastern State of Bihar share what is an added complication. Bihar is mostly rural, with 90 million people living in extreme poverty – the median household income less than 5 USD per day. These people distrust vaccination and anything associated with Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (see more below). According to Nash (2021) medical doctors, usually high caste people, often refuse to treat those with symptoms of respiratory tract infections out of fear of getting Covid, thus even minor respiratory infections go untreated. (Such apathy on the part of any medical staff is parallel to non-treatment practices in the United States during 2020 and much of 2021).

Nash (2021) offers another set of reasons for bad air quality.

“When I lived in Bengaluru, in 2018, air quality was periodically bad due to a mixture of [car emissions], widespread construction – creating a lot of dust, burning [coal or wood] for heat and cooking, and [the common practice of] trash burning, due to a lack of trash collection services.”

Though Nash did not mention it, there are two more factors that amplify the ill effects of trash burning. Whereas traditionally, the burning of natural and biodegradable materials would not be noxious, in modern cities like Bengaluru, people burn plastic, which adds highly toxic particulate matter to the air. And such occurs in a city with a high population density (11,000 per square kilometer, or 30,000 people per square mile), which also lacks adequate green spaces and tree cover to retain moisture and filter the air.

If we cross-reference cities with the highest population density, limited tree cover, poor sanitation, and high poverty, we find a strong correlations with Covid cases – around the world. These include the metropolitan area in and around New York City, areas of the Philippines, the largest cities in India. These same metrics can explain, by contrast, why China might have far lower Covid numbers. Large Chinese cities (places with populations from 2-10 million), which are typically along rivers, reserve significant amounts of land for green spaces and tree cover, there is little to no hunger, and the population densities in Chinese cities are 1/4 to 1/20th of those seen in India and parts of Europe.

Yet, even with the bad air quality, extreme poverty, and inadequate caloric intake, before the vaccines started, India reported low numbers of Covid cases. And, relative to the rest of the world, the numbers are still minuscule. So what has changed for India – from pre-February 2021 to the time since?

Media Reports of a Case-demic and Suppression of Vaccine Deaths

As Nash (2021) explains, In India “Covid stats are collected as a rolling total of cases and deaths rather than an annual total of cases and deaths, as [statistics for] other diseases [are tabulated].” Her point is that daily or weekly news reports sensationalize the figures – without context. Overall in India, according to government statistics, Covid is still not one of the top ten causes of death.

Yohan Tengra (2021) reports that PCR testing has been forced on people in the street in Mumbai as the municipality sought to meet artificial targets of 45,000 tests a day. People with no symptoms were offered a test and they had to comply in order to avoid being fined under the Indian Epidemic Diseases Act. Tengra (2021) argues that in Mumbai (Bombay) over 95% of positives are asymptomatic, while the rest have mild symptoms.

Similarly, in southern India, the Bangalore Mirror reported that 99.4% of recorded Covid cases are asymptomatic. And just as occurred in the United States, Canada, Australia, the UK, and every place with a case-demic, across India, the PCR-CT cycles are set at 35. As the court in Portugal found, at 35 cycles, the PCR results are 97% false positive – and there is no standard for the PCR technology.

And there is more psychological pressure and coercion pushing Indians to get vaxxed. As Tengara (2021) relays, once people are told that they are positive for Covid, even though asymptomatic, cities are placed on lockdown – local officials announce that the only way to return to normal is through mass vaccination. Just like in the United States, the same government PR campaign that tells the Indian public to fear the invisible, tells them to ignore the adverse events caused by the jabs; simultaneously there is a celebrity campaign, urging the public to take the shots, while social media reports of paralysis and death from the jabs, are blocked or dismissed as fake news.

In Tamil Nadu, which has over 78 million inhabitants, only two percent of the population, about 1.6 million people, have taken two shots. Nash (2021) suspects the reception is so low because of a notable death. The popular Tamil actor, Vivek was paid to promote the vaccines. He received the jab on 16 April 2021. The next day, he died of a heart attack. Nevertheless, throughout India, vocal critics of vaccines and masking are arrested – and even denied bail (See Tengara 2021, minutes 7-11).

About iatrogenesis: from typhoid to the use of antiretrovirals (so-called AIDS drugs)

Presently, the State of Maharashtra, which includes the City of Mumbai, has by far the highest number of Covid cases at present. But what are the symptoms, and why would people die? According to Jo Nash, a contact from the State of Maharashtra reported that his grandmother was admitted to hospital with typhoid, but contracted Covid while in hospital. According to the family, the woman died of Covid, but typhoid was written on the death certificate as the cause of death.

Note, in the United States, what others call typhoid (aka typhoid fever), is most often called Salmonella or food poisoning. According to the Mayo Clinic, the symptoms present like the flu: headache, weakness and fatigue, muscle soreness, dry cough, stomach pain, diarrhea or constipation, rash, and dehydration.

The ailment known as of typhoid is common globally, though concentrated in much of Asia. According to Brusch (2019), worldwide there are 21.6 million typhoid cases per year, with 80% of those in Asia – in countries of China, India, Indonesia, Pakistan, Vietnam, Laos, and Nepal. A meta-analysis of 2019 by Marchello et alia found that since the mid-1990s, on an annual basis, Asian countries report over 400 cases per every 100,000 people in a given population. But across the globe, only 200,000 die from Salmonella typhi. That is, the case-fatality rate of typhoid is 1 per 108 or 0.93%, a number comparable to the CFR of seasonal flu.

Regardless of what happened in the case of that grandmother, we should worry about mismanagement and iatrogenesis. I call Covid ‘HIV/AIDS 2.0.’ Recall in most of sub-Saharan Africa, starting in the 1990s to present, a host of symptoms (fatigue, weakness, muscular atrophy, internal bleeding), were/are called a syndrome, and thus diagnosed under the umbrella term of AIDS. Today, the label of choice is Covid.

The worst part is that ever since the creation of the AIDS diagnosis, patients have been subjected to so-called anti-retroviral drugs, instead of nutrition. Some of these same anti-viral AIDS drugs are now given to Covid patients. Two popular drugs include Lopinavir/Ritonavir (Kaletra) and tenofovir/emtricitabine (Truvada).

So we are told that there has been a spike in Covid cases in India. The numbers moved from 13 per million to 159 per million. That data also tracks a sharp rise in all-cause mortality from 10 per 100,000 (in mid-January 2021) to over 90 per 100,000 (in April 2021). Yet both of these numbers coincide with the vaccine rollout. (See video at 1:50).

For those of us who are skeptics of allopaths, the pattern in India of 2021 is remarkably similar the United States for 2020. All patients with respiratory symptoms are diagnosed as having Covid, thus leading to overestimates (thank you Gates-funded modelers), calls for lockdowns, and a push for Pharma’s weapon of choice – vaccines.

Raising the Drawbridge and Closing the Gates?

Bill Gates is famous in the United States. But arguably, the former darling of the Pharma-owned American media, part-time virologist, super vaccinologist, and avowed eugenicist, is more well known in India.

Gates is big in Indian politics and policy – especially subjecting little children to stuff that causes paralysis, pushing Gardasil, and turning India into the vaccine-production hub of the world (thanks GAVI – in partnership with the Bill and Melina Gates Foundation).

Gates does not want to deny vaccines to India. Rather he wants to have a monopoly over sales of vaccine distribution in India. So for Gates, the question is, ‘how to market his final solution (mRNA gene therapy) in search of a problem.’ After all, Gates thinks that there are too many poor brown people, and he is always looking for that 2000% return on his investment. Back in April 2021, in an interview with Sky News (UK) Gates was asked if he thought it would be helpful for nations to lift or waive intellectual property protections on COVID-19 vaccine formulations. His answer was no. That answer surprised a few but should have been expected.

Gates in India: his empire strikes back

As reported in the Hindustan Times of May 2021, India allowed the use of two vaccines: Covishield (the Oxford AstraZeneca mRNA technology) and Covaxin, by the Indian firm Bharat Biotech. It turns about that Gates is already working in India. Of course, he wants to limit or eliminate the competition against his Covishield market share, and Covishield profits, right?

From Jay Hancock, writing in August of 2020, we see how Gates had a long-term goal to corner the Covid vaccine market in India – with her 1.3 billion potential victims. (I wonder when the boosters are coming?)

Hancock (2020) found that in May of 2020, AstraZeneca, CEO Pascal Soriot, said:

“I think [that] intellectual property is a fundamental part of our industry and if you don’t protect IP, then essentially there is no incentive for anybody to innovate,”

With its agent singing the right tune about private profits – at public expense, in June 2020, Gates said: “We went to Oxford and said, ‘Hey, you’re doing brilliant work, but … you really need to team up.’”

In August 2020, Oxford was planning on giving away its vaccines and the formula. A few weeks later, at the urging of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Oxford reversed course. The university signed a deal with AstraZeneca that gave the pharmaceutical giant sole rights and no guarantee of low prices—with the less-publicized potential for Oxford to eventually make millions.

Lest some worry that charity and public health were not the chief aims of their partnership, Hancock (2020) added: (1) the Gates Foundation requires all its grantees to commit to making products “widely available at an affordable price,” a spokesperson said; and (2) AstraZeneca signed deals with CEPI, GAVI and the Serum Institute of India to bring more than a billion doses to low- and middle-income countries.

By December 2020, the entire relationship was summarized by the financial press:

The Serum Institute of India has received US$ 300 million at-risk funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and GAVI (the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization) to develop and make two vaccines, Covishield (by Oxford AstraZeneca) and Covovax by the American firm Novavax. … The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the GAVI, under the Covax alliance, initiated by WHO and other healthcare donor organizations, are going to give [sic] the vaccine at low cost to nearly 192 countries.

So there it is.

Like everywhere else on the planet, India does not have a Covid problem. At their supposed peak, the daily new case rate was 3 people per million inhabitants – for a disease with a 99.7% survival rate. In India, about 25,000 people die per day and going back decades, the historical trend is that 20% die from respiratory ailments and diseases associated with Covid-like symptoms. At its peak, we are told that Indians saw 4,500 Covid deaths per day – or less than the 20% norm.

According to the corporate press, big pharma, and Bill Gates, the people of India are under-vaccinated (a mere 4%, reports NPR).

As it stands, they are not sick, not dying, and just not giving away enough money to the misleadership class.

All I can say is, “Stay strong, and be like India!”

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Like what you’re reading on Vaxxter.com?

Like what you’re reading on Vaxxter.com?

Share this article with your friends. Help us grow.

Join our list here or text DRT to 22828

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

John C. Jones received his law degree (2001) and his Ph.D. is in political science (2003) from the University of Iowa. He has over 15 years of research and writing (both academic and journalistic) in fields of public policy and law, criminal and Constitutional law, and philosophy of science and medicine. His additional areas of expertise and specialized knowledge include applied statistics, etymology, political communications/public relations, litigation and court procedure. He has a particular interest in the science and history of vaccines.